Mahurangi West

14 Jamieson Road

RD 3

WARKWORTH

June 1996

Dear Family,

This is the yarn of the Whale Bone Walking Stick as told by my grandfather, Robert Bell Cole. Being Irish, he was a wonderful teller of tales but I am afraid they pale somewhat when written down as second hand accounts. Unfortunately tape recorders came on the scene too late to record him and even the next generation have been allowed to slip away unrecorded. There is a lesson here for us all - we must chronicle our own oral histories - do it while we can. I am convinced, that even though our stories may seem insignificant to us now, they will enrich our descendants" lives, just as the tales from our forbears have enriched ours.

My recollection of this yarn is reinforced by having heard it retold many times by my father, Mac. I also have a copy of a version Bill Cole wrote and I had corresponded with Dick Cole on the subject. I have extended this work with some related information and include references. You should be able to borrow the publications I have mentioned through your local library. If you come across anything else yourself, please let me know.

I would like to thank Bob Mertens for his valuable advice; John Cole for searching for Splendid photos and his proof-reading services; my daughter Noeline Cole for teaching me how to use the computer and sorting out the many problems I have encountered. I find it amusing to contemplate the changes that have taken place between the generations: When I was young, one of my greatest fears was that I might have to say to my father, "Dad - I've crashed the car!" Now I dread having to say to my daughter, "Help - I've crashed the computer!"

Yours faithfully,

Michael McMurray Cole

THE WHALEBONE WALKING STICK

When my grandfather, Robert (Bob) Bell Cole was seventeen years of age he emigrated to the Chatham Islands in New Zealand to work as a farm cadet for his second cousin, Thomas Ritchie, who had a large cattle run there. Bob was the only passenger aboard the 761 ton barque Lurline, making a passage of 93 days, to arrive in Christchurch on the second day of August, 1879. He worked for Ritchie for four years.

While he was on the Chathams the Yankee whaler Splendid called at the island for firewood and potatoes. Some of the ship's crew were confined in irons for attempted mutiny on the high seas and were to remain so until brought to trial at the end of their voyage. As a consequence, the company was short-handed for the task of lightering and stowing the cargo. Bob joined a work party of farm labourers organised to help do the job. Part way through the day they took a break from work and the older men went below for a drink. Bob filled in time by wandering forward to the fo'c'sle-head to where the sailors in chains were sitting on the deck. When he spoke to them in greeting, one of the men, a Scot, commented on Bob's North of Ireland accent and said that he had been there only once, to a small place called Portaferry. Bob told him that Portaferry was where his mother came from. The sailor then asked his name. On hearing that it was Cole he then wanted to know whether, by any chance, he was the son of Jane Coates and John Cole. To his amazement he was!

The sailor introduced himself as John Grant, then went on to relate the following tale. In 1855, when he was just a lad, his uncle took him aboard his coastal trading ship as an apprentice. One of its destinations was the small landing at Portaferry. It was a fine August morning and having nothing better to do while waiting for the ship to be worked, he went ashore, wandered through the village and out into the countryside. He stopped in a lane to watch some men gathering hay. They invited him to lend a hand because they feared the weather was about to change for the worse. He promptly scrambled over the stone wall and joined in with a will, soon becoming absorbed in the bustle to get the hay stacked before the rain began. Henry Coates, the owner of the farm, was on top of the hay stack from where he could see the harbour and when the job was complete he called down to the boy and asked him the name of his ship.

On being told, he said that she has just sailed. The sudden weather change had obviously precipitated a hasty departure. The boy burst into tears of mortification. On his very first voyage the worst imaginable thing had happened - he had missed his ship and become stranded - a stranger in a strange land. Henry Coates, who happened to know the captain, assured him that he could stay with them until the ship called again some weeks hence.

Henry's daughter Jane took special care of the boy, treating him like a son. During that time a John Cole, whose home was "Clontivern" in County Fermanagh, about forty miles distant, was courting Jane Coates. When the ship returned to Portaferry, Henry Coates and Jane escorted the lad aboard and gave the captain an explanation of the circumstances. He readily accepted their story and assured them that the boy would receive no punishment. So they said their farewells and John Grant left, promising to come again to visit them when next his ship called. However it was never to be.

The sailor then told Bob that down in the fo'c'sle he had a whalebone walking stick that he had made as a wedding present to Bob's mother who had been so kind during his stay in Ireland. In all these years, however, he had not had the opportunity to deliver it. He sent Bob below to the confines of the crew's quarters to fetch the stick and asked him to make sure it reached his mother as he feared he would never see Ireland again. Bob gave his word that he would do as he asked.

In about 1890 Bob's brother, David Cole of Auckland, took the stick home to Ireland and presented it to Jane and John Cole. After they died, James McMurray (by then the Chief Dispensing Chemist at the Royal Belfast Infirmary) decided it should be returned to New Zealand to the eldest living son, Bob Cole. David Cole sent it down to Te Kuiti in 1937. Bob Mertens was living at the Coles" when the stick arrived and had the job of unpacking it from a neat custom-made plywood box, fastened with small panel pins.

After Bob Cole died in 1955, the stick was in his son Mac's care for many years until, at a family reunion, he gave it to his brother Bill. Bill later passed it on to Mac Cole's eldest son Michael.

NOTES

Jane Coates and John Cole married on the 17th February, 1857. On 13th August, 1861 their third son was born and christened Robert Bell Cole. He became known later as "Bob" and was often referred to in the third person as "RB". The Maoris in the King Country called him "Mr. Bob."

In 1879 Bob arrived in the Chathams, a small isolated group of wind-swept islands in the Pacific, six hundred miles east of Christchurch. When relating this story, he referred to the Splendid as being a "Yankee whaler" which in fact she was. According to Harry Morton in the book, "The Whale's Wake", the ship was purchased in 1877 by Elder and Nicol of Dunedin, so was in New Zealand ownership at the time of our story. This raises the question as to where John Grant was destined to go in his chains - America or New Zealand? I had always assumed America but this is obviously incorrect. I have yet to check in Tasmania on the possibility that he was convicted and sent there because that is where he eventually retired.

The Second Mate aboard the Splendid was George Cook of Auckland who for many years wrote whaling stories for the Auckland Weekly News under the nom de plume of "Lonehander." Bob corresponded with him and I have a letter of reply dated 4th of July, 1934 from 29 Aitken Terrace, Glenmore, Kingsland in Auckland. He says:

"The Jack Grant you mentioned was one of the whitest men I ever sailed with, "Bucko". I have a correspondent in Hobart who knew Bucko well and he has given me the latter part of the old-timer's career - He died at Macquarie Harbour, Tasmania."

Cook mentions efforts to form an Historical Society in Auckland, giving Mr. A.B. Chappel, c/o the N.Z. Herald, as the contact for information. He also said he knew Mr. Ritchie by reputation only. He thanked Bob for adding to his information. It is possible Bob's letters have survived with Cook's papers in some archive in Auckland.

Bob described John Grant as being "an old man". We could assume Grant was perhaps 14 years old when in Ireland in about 1856. This would then make him about 40 when Bob met him in the Chathams and he could well have looked much older as the result of what had been, no doubt, a most rigorous life at sea.

THE WHALER SPLENDID

Note the catch boat hanging in davits ready for action at a moment's notice as was the practice in all but the worst weather. The flue stack amidships is from the try boiler used to render the blubber. The decks and fittings, except for the main mast, were thoroughly scrubbed down after each catch. They considered that washing the main mast would wash away their luck.

According to a description of the Splendid in "Lost Leviathan", she was barque rigged with square sails on the fore and mizzen masts; fore and aft sails on the main. The fore and aft decks were flush and she had the long, steeply raked bowsprit, typical of Yankee whalers.

The crew's quarters in the fo'c'sle were dingy and confined, with three tiers of narrow bunks running into the angle of the forepeak. One small oil lamp swung from the deckhead and an oil stove provided heat. They lived a terribly hard life and were paid twenty cents per day plus a one two-hundredth "lay" or share of the catch. After three years away and a reasonable haul, this could amount to as much as thirteen pounds per man. However there were deductions made for items such as clothing and tobacco, often valued at inflated rates, to result in a meagre final payout.

Dick Cole told me he once read an exciting book entitled "The Cruise of the Catchalot" by F.T. Bullen that detailed its sperm whaling exploits. When he discussed it with his father, he told him that he had also read and enjoyed the yarn. He said "Catchalot" was really a non de plume for the Splendid of Chatham fame and was also an alternative name for the sperm whale, which was the most lucrative to catch.

He also read book about the life of Albert Cook, (which I have been unable to trace). He was part Maori and a wonderful person to whom everyone took an instant liking. He sailed as First Mate for many years out of Southland on the Splendid, then in New Zealand ownership. He finally left her and went whaling on his own account at Whangamumu on the east coast of the Bay of Islands and then later at Russell. Dick said he was the only person in the world to use wire nets to catch whales. I have a copy of an illustration from the 1901 Christmas edition of the Auckland Weekly News entitled, "Capturing a whale with the aid of a net at Messrs. H. F. Cook and Co.'s station, Wangamumu, Northern New Zealand."

Bob was an avid reader of seafaring stories and often quoted from them. He knew all the names for the masts, spars, sails and rigging of a sailing ship. He had a number of whaling books in his library that I read at a young age but can no longer remember in detail.

"THE CRUISE OF THE CATCHALOT"

This is an account of the adventures of the author, F.T. Bullen, while sailing around the world catching whales on the ship Splendid. The voyage took three years.

As Dick said - he used "Catchalot" as the nom de plume for the Splendid and also gave fictitious names for the crew. During the circumnavigation he called at Russell, Cook Strait and Bluff in New Zealand.

While in the Northern Tongan Island group of Vava'u, Bullen had a very dramatic encounter with a whale that followed their catch boat into a sea cave. He described the place in detail. It seems to be the famous Swallow Cave that Margaret and I are familiar with from our visits there. As far as we know there is no other similar cave in the group. If this is so, then his description of the area seems highly exaggerated - fanciful in the extreme - which leads me to doubt some of what he says elsewhere in the book.. And yet, his account of Raol Island, another place I know well, is completely accurate. I imagine his details of the ship and its gear are possibly closer to the truth and worth noting.

He considered the Catchalot to be less graceful than British ships on which he had sailed. She was "built by the mile and cut off by lengths as you want them." Her masts poked up as straight as broom sticks and the bow-sprit rose at about forty-five degrees. (The angle is a little less than that as can be seen in photographs.) The try-works was a "ten by eight-foot erection of brickworks" that had an air space and water bath beneath it to prevent the deck catching fire. They detached the metal flue when under sail.

On that voyage the Catchalot carried a total complement of thirty-seven. Twenty-four were "Before the Mast" or ordinary seamen. They were a very motley bunch of mixed nationalities and few had ever been to sea before. Half the crew were described as "Black." They lived in the cramped fo'c'sle. Access from the deck was down a steep ladder. The only illumination was from a single teapot lamp that gave out more smoke than light. The place contained a "villainous reek." By mutual consent, blacks bunked on the port side and whites the starboard. They picked up extra hands at Tahiti - "Kanakas" he called them - and dropped them off in Tonga. They were unsuccessful in recruiting more for the New Zealand leg. It did not explain where these natives were quartered.

Conditions were extremely hard and discipline harsh. One man was caught stealing and received two dozen lashes, after which they doused his wounds with salt water. He was tied to the weather rigging by the thumbs using thin fishing cord, so that his toes just reached the deck. Every roll of the ship swung him off his feet. When he finally fainted his companions were allowed to cut him down and revive him. On top of all this he had to stand the remainder of his watch.

When punishment was due to be meted out, a whip was made by tying lengths of knotted fishing cord to a wooden handle. Sailors had to be dying before considering going on sick parade as they risked punishment for malingering. The food was appalling and it was a welcome relief to catch dolphin that after slaughtering were hung to mature, the texture and flavour improving after a few days. Delicacies such as liver and brain went to the gentlemen aft.

They worked all day, every day. Catching and processing a whale was a long and arduous task, each one taking a week or more, during which time boiling down continued day and night. When completed, everything was thoroughly scrubbed down and the deck holystoned. Between catches the topsides were kept immaculate, mainly, Bullen suspected, to keep the crew occupied. There was a general tradition that the crew be given twenty-four hours shore leave plus a portion of their pay every three months. On Bullen's entire trip they only got ashore two or three times other than in work details.

One such time was in the Bay of Islands where half the crew were allowed ashore on one day and the other half the next. Observers from the ship noticed that soon after landing, most of the men were seen to be lying unconscious on the beach, having spent only a fraction of their money on grog. A boat was dispatched to gather them up because they feared the local Maori might rob them.

Obtaining wood and water was their principal requirement whenever reaching land. Cutting down trees and getting fire wood onboard was very heavy work. Water collecting was made easier by stringing the water barrels together, cleverly rigged, so that they towed upright in line behind a rowboat.

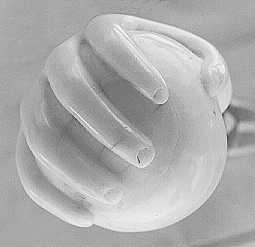

The main diversions aboard were rope work and scrimshaw. The ship's carpenter was famous for making walking sticks and as soon as they had processed their first whale he started four sticks. As with the Cole stick, he employed a whale tooth as the handle. His speciality was to carve it to resemble rope work. The main tool used was manufactured by heating an old file in the fire so that teeth could be filed in one edge to serve as a saw. Shaping and carving was done using old knives, sail needles and chisels. They polished the finished product with oil and whiting if available, otherwise they used powdered pumice. The shafts were as true as if done on a lathe, but of course there was no lathe on board.

Production from whaling peaked in 1837. (There were 635 American ships working in 1859.) The American Civil War in 1861 brought them to a complete stop. Whaling then became more and more difficult as the numbers of sperm whales went into rapid decline.

The stick John Grant made was fashioned from the rib of a whale and inlaid with paua and tortoise shell. The handle was carved from the tooth of sperm whale, the core of which is clearly discernible. Lottie's husband, Harry Middelton, replaced some of the missing paua shell inlay.

In his later years Bob Cole and his wife Blanche lived in the cottage adjacent to Mac and Noeline Cole's home at Tammadge Street in Te Kuiti. The walking stick hung beside his bed as his most treasured possession.

From about 1857 on, there was increasing competition from petroleum oil. No doubt these factors and the age of the Splendid made it affordable to the New Zealand buyers. In "Sealers and Whalers", page 147, there is an indistinct photo of the Splendid at Half Moon Bay, Stewart Island, taken when she was already fifty years old. She was poorly maintained and in 1890, was condemned and dismasted at Port Albert on the Kaipara Harbour

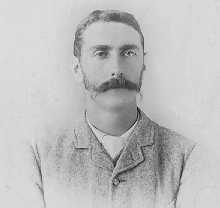

Thomas Ritchie

From "The Chatham Islands their Plants Birds and People" by E.C. Richards. Published 1952, Simpson & Williams, Christchurch.

Thomas Ritchie and his brother leased Owenga from the Maoris in 1865, thereby becoming two of the earliest runholders on the Chathams. Thomas also bought Kaingaroa on the North Coast.

The run was mostly stocked by horses with an Arab strain from the stallion and mares imported by Pomare in 1840. Ritchie also bought any horse offered to him by the Maoris and engaged jockeys to train them. He cultivated portions of his land with the most modern of implements of which, however, he took no care. Wheat did very well on the bush land and he got wonderful crops from everything he grew but nothing could save him from bankruptcy, not even the wrecks which he generally bought for a mere song.

Just before the end came he married a girl from a draper's shop in New Zealand. She was the admiration of the Island for the splendid way she stuck to him. Instead of his big house at Kaingaroa they lived in a hovel on the Waitangi beach and were fed through the bounty of the Maoris for several years; then she took him and the children to New Zealand where her people lived, and there he died.

[At the time that RB Cole worked on the Chathams, Ritchie had a Maori "wife" and RB held her in the highest regard.]

===================================================

The following information is taken from a book lent to me by Denise Aylward

"A Land Apart - The Chatham Islands of New Zealand" by Michael King with

photographs by Robin Morrison.

Sheep had been introduced to the Chathams in the early 1840s ...... It was a group of young men who reached the Chathams in the 1860s who were the first to make use of the "clears" there ( the areas of native grass and fern that occurred in the bush and among the bracken on the peat flats). One of the first who came was Thomas Ritchie, an ebullient Northern Irishman who came to the Chathams for a visit in 1864, at the age of 20, and stayed for nearly 60 years.

Ritchie decided to take up 80 acres on Okawa point, which he leased from the Maori chief, Katene. "I am Katene's Pakeha and every native respects me as such," he wrote at the time......

By the late 1860s he owned over 9,000 hectares of land at Owenga, on which his brother [Robert] ran sheep, and he leased a further 4,450 hectares at Kaingaroa" to the north of Okawa where he built Lake House on the shores of Lake Te Wapu - the most luxurious home seen on the Chathams up to that time. [ There is a photograph showing the house with Ritchie and his two sisters on the verandah.] Eventually he was running 16,000 sheep on these properties and a third on the south-west Ngaio coast.....

The Native Land Court hearings of 1870 recognised the [Taranaki groups], Ngati Mutunga and Ngati Tama claims to 97 per cent of Chatham Island...... Subsequent land sale and leasing could only be carried out with the consent of Maori owners...... Some European settlers feared..... being killed...... or at least being driven off the lands they were leasing. On one occasion, in 1872, the entire Pakeha population of the island barricaded itself into Ritchie's house at Kaingaroa, fearful of massacre.

Edward Reginald Chudleigh became a neighbour of Ritchie's...... [He was described as being] respectable but not respected. The Maori and Moriori new him as Kau (cow). Other Europeans on the Island disliked him: he was judgemental, sanctimonious, and "superior". He fell into dispute - and often into litigation - with almost every person with whom he had to deal...... But where Ritchie was warm, sociable and trusting, Chudleigh was cold, misanthropic and paranoid.

There is no surviving record of what Ritchie thought of Chudleigh, though there is ample evidence for speculation. Chudleigh's views of Ritchie, however, are recorded and conveyed to posterity through his diary. "T.R. is about the most thoroughly bad man I know," (16 September 1881). "He has turned his sisters into the kitchen and lives rampant with prostitutes and brandy," (8 November 1882). "Thomas Ritchie has been having a glorious drunk since the Omaha sailed. He must have had a glorious constitution to be alive," (2 April 1886).

In the end Chudleigh may have had the last laugh...... Ritchie over-reached himself and lost the fortune he had made from sheep, trading, retailing and salvage.

By the early 1890s he was penniless and living in a small cottage at Okuki north of Waitangi...... Chudleigh remained prosperous...... Ritchie lived a decade longer: and every time the Chatham Islands Jockey Club, which he had founded, held its annual races, the Northern Irishman was remembered for his generosity and his joie de vivre. It is a moot point which epitaph was more to be desired.

Ritchie founded the Chatham Islands Jockey Club in 1873...... It is now the oldest continuously operating racing club in New Zealand. He also initiated annual shooting competitions on the western end of Waitangi beach. Other entrants decided early on that it was best to let Ritchie win, because the subsequent shout at the pub would be larger and longer.

After Thomas Ritchie went bankrupt in the early 1890s, the Owenga station , as it came to be known, passed through various hands until bought by the crown in the mid-1950s.

The Government balloted it for returned servicemen, and the successful applicant was Alfred "Bunty" Preece, grandson of the Moriori leader Riwai te Ropiha. Thus did a major piece of Chatham Island real estate, wrested from the Moriori by conquest, pass back into Moriori ownership. The Barkers took over the Kaingaroa station in the 1890s and the family are still farming it to this day.

===================================================

Bob's employment with Ritchie came to an abrupt end when he was accused of stealing a saddle. It was a special fancy light-weight thing Ritchie had recently purchased from the Mainland. Bob was as honest as the day was long. Deeply offended, he marched straight aboard a whaling ship and was off. They engaged him as an extra unpaid crew member for the time it took to reach New Zealand. He had to sleep on deck in his clothes with a single grey blanket pulled over his head. Sleeping with a blanket over his head became a life-long habit.

The Cole and Ritchie families in New Zealand have kept in close contact down through the years and generations; the Chatham Islands have held a special fascination for many of us - any starters for a pilgrimage?

===================================================

REFERENCE MATERIAL:

There should be the original photograph of the barque Splendid in the Kinnear collection in the Alexander Turnbull Library (Ref: 16340 1/4) but a Wellingtonian friend of John and Betty Cole reported that it is missing from the files. They obtained a photocopy. I was eventually able to get a good copy from the Auckland Public Library, from "Sealers and Whalers in New Zealand Waters", page 124, which is the one reproduced here on page 5.

Lost Leviathan - Whales and Whaling by F.D. Ommanney,

Auckland Central Library.

Ref: CST 639.28 055.

The Whale's Wake by Harry Morton, Auckland Central Library.

Also available at the Auckland Museum Library.

Lonehander by George Cook, published in the Weekly News.

(I have yet to check the NZ Herald Archives.)

Whaling and Sealing in the Chatham Islands by Rhys Richards.

His bibliography includes reference to the Thomas Ritchie Manuscript Collection.

Auckland Central Library.

Ref: NZP 639.2 R71.

Also at Auckland Museum Library.

Whaling Logbooks and Journals 1613- 1927 by Stuart C. SHermann,

Garland Publishing, contains lists of Logs. Splendid's logbooks are only available in this record from 1843 to 1872.

Voyages and Wandering in Far Off Seas and Lands by Thomas J. Inches, published by Headly Brothers, London.

Auckland Museum Library.

Whaling in Southern Waters, Auckland Central Library.

Ref: 639.28 T63. (Could not find.)

Cruise of the Catchalot by F.T. Bullen, Auckland Central Library.

Ref: 910.4.

First published in 1898, it may deal with a time much later than Bob's Chatham period. However, as his voyage begins in America, I am inclined to think it refers back to an earlier period. I have so far been unable to borrow a copy but have skim read it at the library.

Thomas Ritchie Manuscript Collection, 1846-1930, Canterbury Public Library.

There are Logbook records of the Splendid in the Old Dartmouth Historical Society, New Bedford and at the Nantucket Historical Society, Mass. USA. Presumably these are the same as those available on microfilm from the National Library in Wellington.

An Historical Society of Auckland was established in the 1930s but went into recess during the war. Mr. John Webster of the present Auckland Historical Society told me their organisation formed in about 1954 and has scant record of that first society. They have no knowledge of any records of George Cook. He has, however, given me a couple of leads to follow.

Contact us at cole@familycole.net Return to Home Page